Not Any More Accurate But a Whole Lot More Confident

What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact. - Warren Buffet

In 1974, Paul Slovic, a world-class psychologist and a peer of Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman (author of Thinking Fast and Slow, highly recommended!), decided to evaluate the effect of information on decision making. Slovic gathered eight professional handicappers and asked them to predict the winners of horse races. The task was to predict winners of 40 horse races in 4 consecutive rounds. In the first round, the gamblers would be given five pieces of information of their choice on each horse that would vary from handicapper to handicapper. E.g., one handicapper might ask for the jokey’s years of experience, while another might ask for the horse’s age or the fastest speed achieved by a horse. Slovic asked them to predict not only the winner of each race but also their level of confidence in their prediction.

There were ten horses in each race, so even if they were making blind guesses, each handicapper should be right 10% of the time on average. And their confidence in these blind guesses should also be 10%. As the experiment began, in Round 1, with five pieces of information, the handicappers were 17% accurate, and their confidence was 19%. Their performance was much better than the blind guesses, for sure. In Round 2, they were given ten additional pieces of information; in Round 3, twenty. And in the final round, 40 additional pieces of information.

Surprisingly, their accuracy of predicting the winner had flatlined at 17%. They were no more accurate in their prediction, despite getting all the additional information. But their confidence in their prediction increased from 19% in Round 1 to 34% by Round 4.

The additional information made them no more accurate but a whole lot more confident. If they were betting real money, they would surely lose a lot of it.

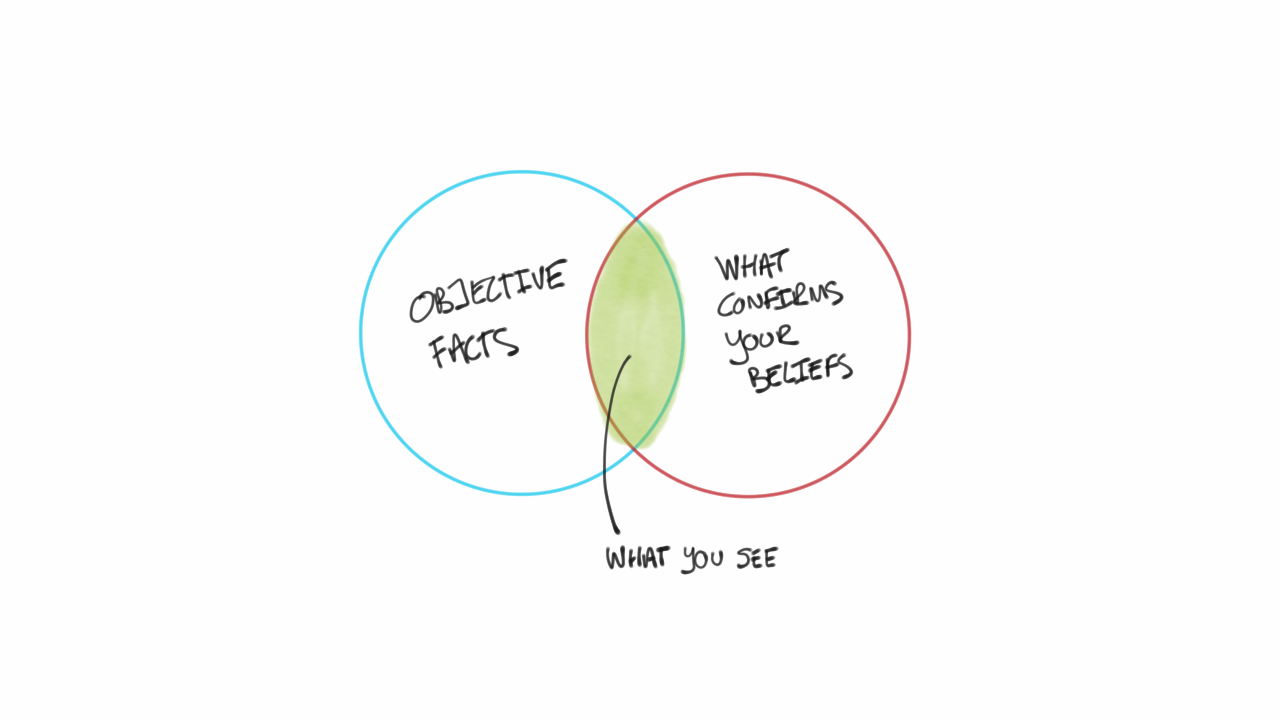

Beyond a certain minimum, additional information only feeds what psychologists call Confirmation Bias.

Image Credits : fs.blog

Image Credits : fs.blog

As we start consuming new information about a topic, we start to develop a hypothesis. But once we have a hypothesis, we no longer remain objective towards new facts. Any additional information that confirms our belief makes us more certain of our conclusion, and hence we accept it. And we conveniently disregard the facts that conflict with our hypothesis.

You must have observed this all the time in your respective areas of work too.

As someone involved closely with the Revenue function, I have seen this play out many times. Here is the objective fact - It’s the low season; competition has dropped their prices. Revenue team’s interpretation - We should drop prices immediately; we have seen this work well in other geographies too; a drop in prices leads to an increase in demand; ours is a very price-sensitive market. The city team’s view - We should not drop prices; it’s already low season, people won’t start traveling just because the prices are low; our city works differently. And remember last year when we dropped prices, it didn’t have any positive impact.

It’s interesting to note how the additional information has so little impact on influencing each party’s belief. This tendency to interpret information that confirms our existing belief is a problem with beginners and experts alike. Even the great Albert Einstein fell prey to this.

Considered the founding father of Quantum Physics, Einstein made groundbreaking discoveries in the early 1900s. He developed the Special Theory of Relativity (E = mc2) and light as Qantas, which led to his Nobel prize winning discovery of the Photoelectric effect. But as he grew older, he had trouble accepting new theories built by younger scientists on top of his work.

Neils Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and Ervin Schrodinger proposed that in the Quantum Realm (at the sub-atomic level), entities - such as electrons - had only probabilities if they weren’t observed. It means that an electron does not have a definite position or path until we observe it. Einstein, on the other hand, didn’t believe in this probabilistic view of the world. He believed that an objective reality existed whether or not it was observed; he famously quoted that God doesn’t play dice with Universe. He believed that all of nature - Gravitation, Electromagnetism, time and space, and even sub-atomic complexity - can be explained by a single equation, which he called Unified Theory of Relativity.

Even though the evidence kept mounting against it, Einstein held on to his belief that all of the Universe can be explained by one single equation. In the Solvay convention of 1927, he kept on trying to disprove all the new theories with his thought experiments that confirmed his view. He spent the rest of his life trying to come up with such an equation but unfortunately could never prove it.

In his book The Little Book of Stupidity, Sia Mohajer writes that confirmation bias is so fundamental to our development and reality that we might not even realize it is happening.

That’s what makes it the most difficult of biases to overcome. Perhaps, the only way to overcome it is to hear as many conflicting views as possible and constantly check if you are interpreting new information objectively.

Best,

Kaddy

PS - If you are interested in the history of Quantum Physics, I highly recommend this article. If you want to geek out further, Walter Isaacson’s biography of Einstein will blow your mind.